Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Reviewed by

&Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

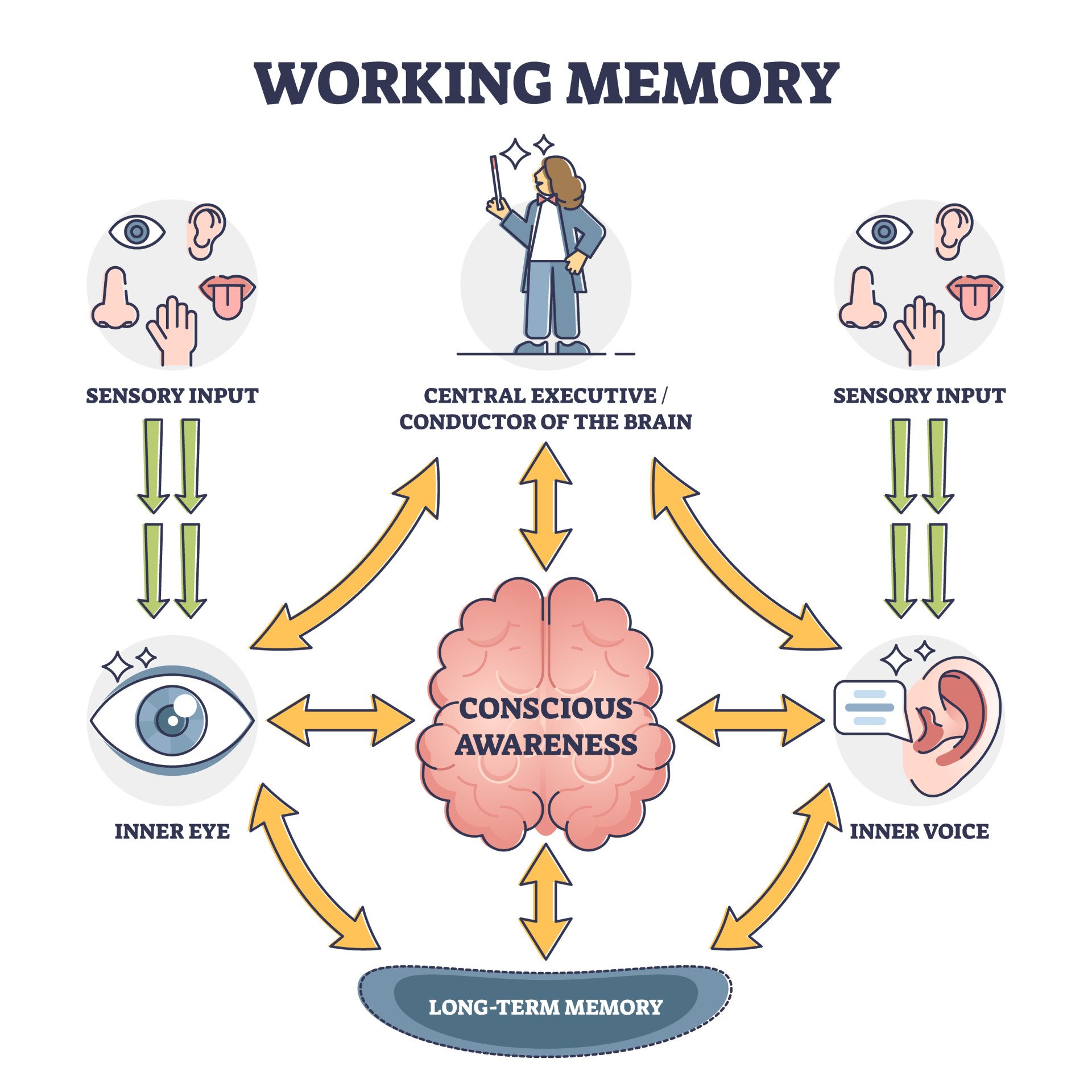

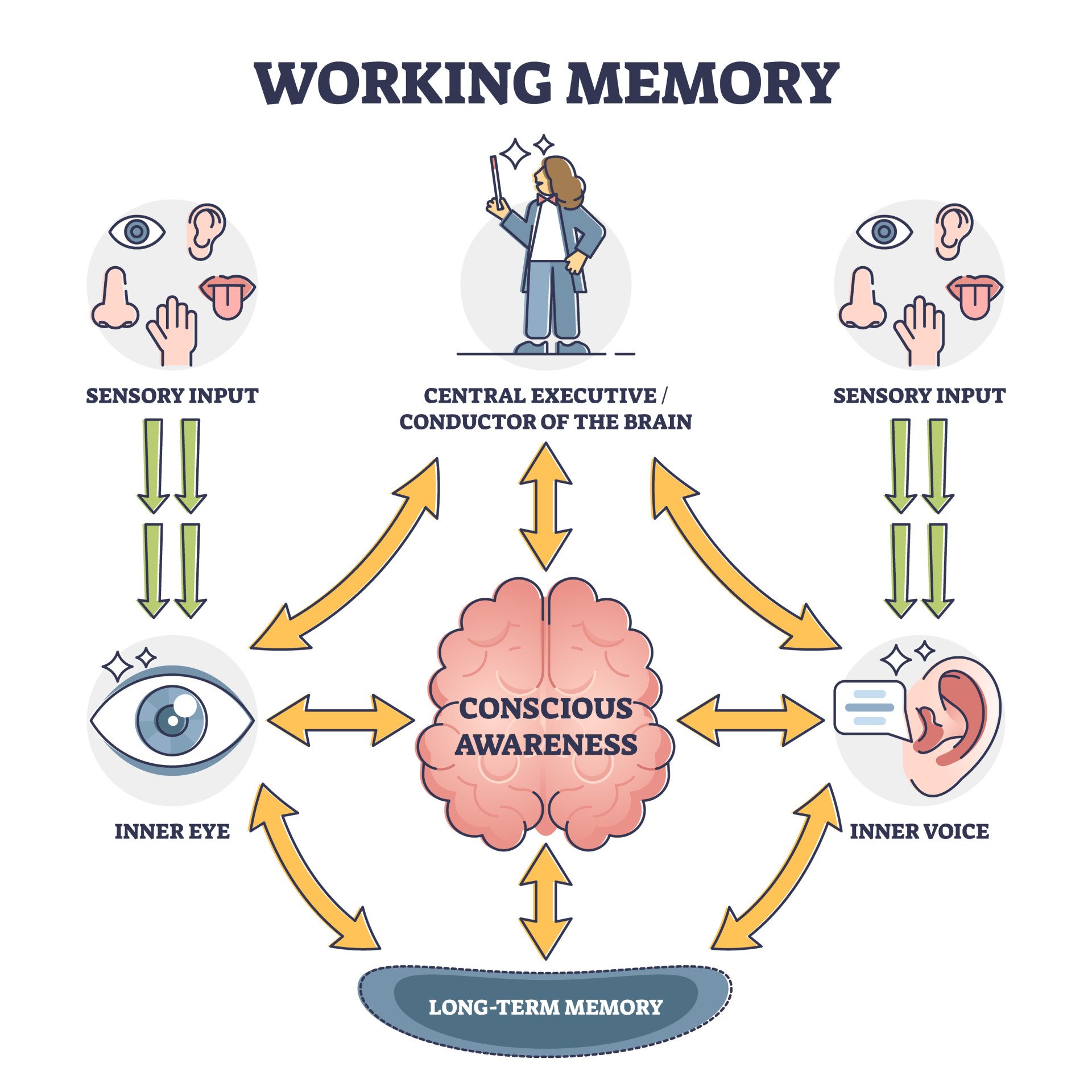

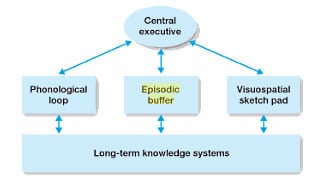

The Working Memory Model, proposed by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974, describes short-term memory as a system with multiple components.

It comprises the central executive, which controls attention and coordinates the phonological loop (handling auditory information), and the visuospatial sketchpad (processing visual and spatial information).

Later, the episodic buffer was added to integrate information across these systems and link to long-term memory. This model suggests that short-term memory is dynamic and multifaceted.

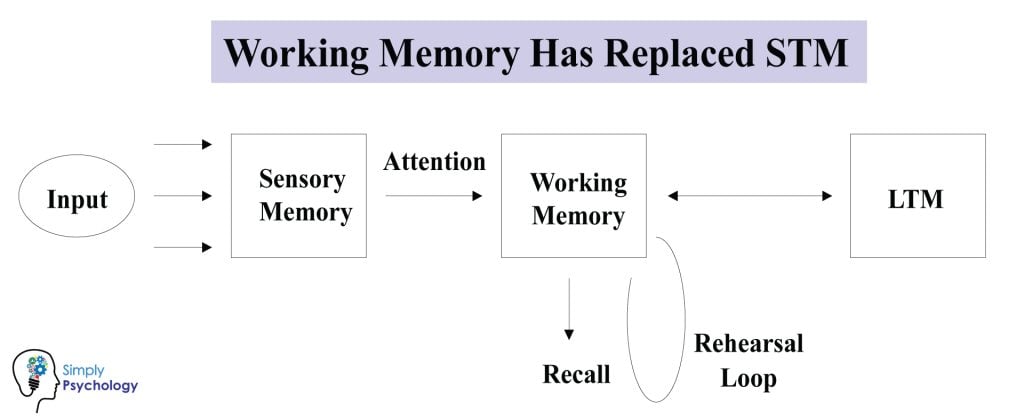

Atkinson’s and Shiffrin’s (1968) multi-store model was extremely successful in terms of the amount of research it generated. However, as a result of this research, it became apparent that there were a number of problems with their ideas concerning the characteristics of short-term memory.

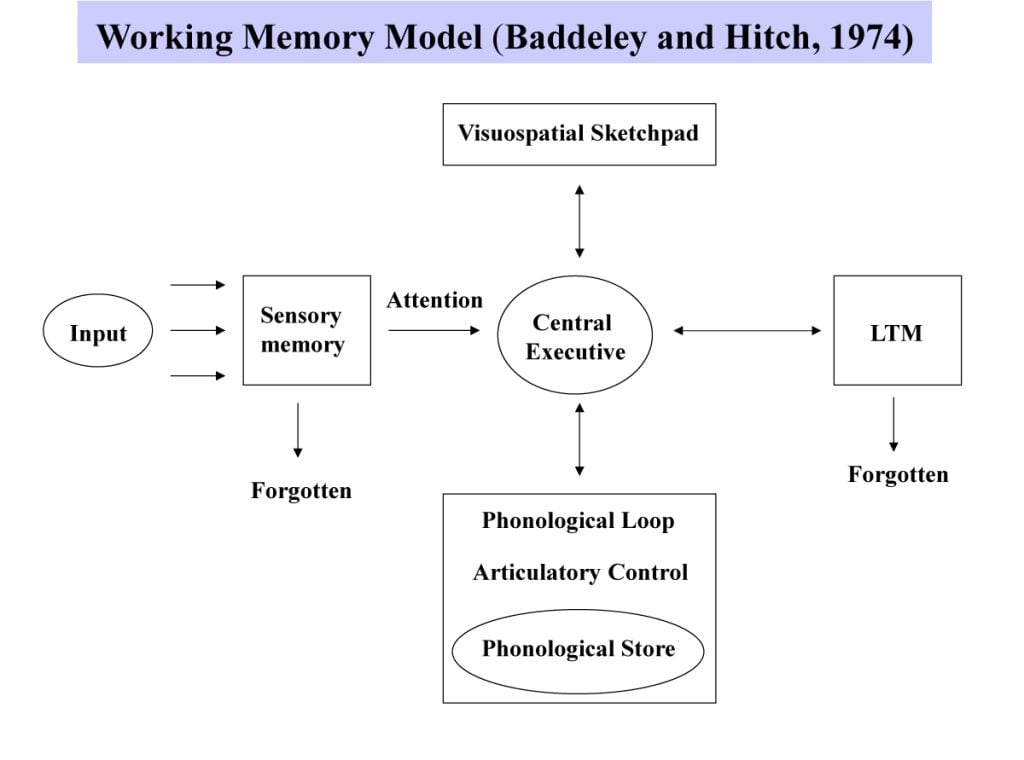

Fig 1. The Working Memory Model (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974)

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) argue that the picture of short-term memory (STM) provided by the Multi-Store Model is far too simple.

According to the Multi-Store Model, STM holds limited amounts of information for short periods of time with relatively little processing. It is a unitary system. This means it is a single system (or store) without any subsystems. Whereas working memory is a multi-component system (auditory and visual).

Therefore, whereas short-term memory can only hold information, working memory can both retain and process information.

Working memory is short-term memory. However, instead of all information going into one single store, there are different systems for different types of information.

Drives the whole system (e.g., the boss of working memory) and allocates data to the subsystems: the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad.

It also deals with cognitive tasks such as mental arithmetic and problem-solving.

The visuospatial sketchpad is a component of working memory model which stores and processes information in a visual or spatial form. The visuospatial sketchpad is used for navigation.

The phonological loop is a component of working memory model that deals with spoken and written material.

It is subdivided into the phonological store (which holds information in a speech-based form) and the articulatory process (which allows us to repeat verbal information in a loop).

Fig 2 . The Working Memory Model Components (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974)

The labels given to the components (see Fig 2) of the working memory reflect their function and the type of information they process and manipulate.

The phonological loop is assumed to be responsible for the manipulation of speech-based information, whereas the visuospatial sketchpad is assumed to be responsible for manipulating visual images.

The model proposes that every component of working memory has a limited capacity, and also that the components are relatively independent of each other.

The central executive is the most important component of the model, although little is known about how it functions. It is responsible for monitoring and coordinating the operation of the slave systems (i.e., visuospatial sketchpad and phonological loop) and relates them to long-term memory (LTM).

The central executive decides which information is attended to and which parts of the working memory to send that information to be dealt with. For example, two activities sometimes come into conflict, such as driving a car and talking.

Rather than hitting a cyclist who is wobbling all over the road, it is preferable to stop talking and concentrate on driving. The central executive directs attention and gives priority to particular activities.

p> The central executive is the most versatile and important component of the working memory system. However, despite its importance in the working-memory model, we know considerably less about this component than the two subsystems it controls.

Baddeley suggests that the central executive acts more like a system which controls attentional processes rather than as a memory store. This is unlike the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad, which are specialized storage systems. The central executive enables the working memory system to selectively attend to some stimuli and ignore others.

Baddeley (1986) uses the metaphor of a company boss to describe the way in which the central executive operates. The company boss makes decisions about which issues deserve attention and which should be ignored.

They also select strategies for dealing with problems, but like any person in the company, the boss can only do a limited number of things at the same time. The boss of a company will collect information from a number of different sources.

If we continue applying this metaphor, then we can see the central executive in working memory integrating (i.e., combining) information from two assistants (the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad) and also drawing on information held in a large database (long-term memory).

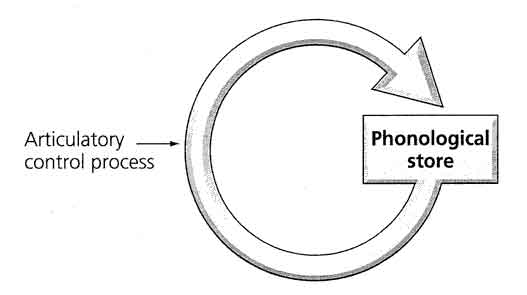

The phonological loop is the part of working memory that deals with spoken and written material. It consists of two parts (see Figure 3).

The phonological store (linked to speech perception) acts as an inner ear and holds information in a speech-based form (i.e., spoken words) for 1-2 seconds. Spoken words enter the store directly. Written words must first be converted into an articulatory (spoken) code before they can enter the phonological store.

Fig 3 . The phonological loop

The articulatory control process (linked to speech production) acts like an inner voice rehearsing information from the phonological store. It circulates information round and round like a tape loop. This is how we remember a telephone number we have just heard. As long as we keep repeating it, we can retain the information in working memory.

The articulatory control process also converts written material into an articulatory code and transfers it to the phonological store.

The visuospatial sketchpad (inner eye) deals with visual and spatial information. Visual information refers to what things look like. It is likely that the visuospatial sketchpad plays an important role in helping us keep track of where we are in relation to other objects as we move through our environment (Baddeley, 1997).

As we move around, our position in relation to objects is constantly changing and it is important that we can update this information. For example, being aware of where we are in relation to desks, chairs and tables when we are walking around a classroom means that we don”t bump into things too often!

The sketchpad also displays and manipulates visual and spatial information held in long-term memory. For example, the spatial layout of your house is held in LTM. Try answering this question: How many windows are there in the front of your house?

You probably find yourself picturing the front of your house and counting the windows. An image has been retrieved from LTM and pictured on the sketchpad.

Evidence suggests that working memory uses two different systems for dealing with visual and verbal information. A visual processing task and a verbal processing task can be performed at the same time.

It is more difficult to perform two visual tasks at the same time because they interfere with each other and performance is reduced. The same applies to performing two verbal tasks at the same time. This supports the view that the phonological loop and the sketchpad are separate systems within working memory.

The original model was updated by Baddeley (2000) after the model failed to explain the results of various experiments. An additional component was added called the episodic buffer.

The episodic buffer acts as a “backup” store which communicates with both long-term memory and the components of working memory.

Fig 3 . Updated Model to include the Episodic Buffer

Researchers today generally agree that short-term memory is made up of a number of components or subsystems. The working memory model has replaced the idea of a unitary (one part) STM as suggested by the multistore model.

The working memory model explains a lot more than the multistore model. It makes sense of a range of tasks – verbal reasoning, comprehension, reading, problem-solving and visual and spatial processing. The model is supported by considerable experimental evidence.

The working memory applies to real-life tasks:

The KF Case Study supports the Working Memory Model. KF suffered brain damage from a motorcycle accident that damaged his short-term memory.

KF’s impairment was mainly for verbal information – his memory for visual information was largely unaffected. This shows that there are separate STM components for visual information (VSS) and verbal information (phonological loop).

The working memory model does not over-emphasize the importance of rehearsal for STM retention, in contrast to the multi-store model.

What evidence is there that working memory exists, that it comprises several parts, that perform different tasks? Working memory is supported by dual-task studies (Baddeley and Hitch, 1976).

The working memory model makes the following two predictions:

1. If two tasks make use of the same component (of working memory), they cannot be performed successfully together.

2. If two tasks make use of different components, it should be possible to perform them as well as together as separately.

Aim: To investigate if participants can use different parts of working memory at the same time.

Method: Conducted an experiment in which participants were asked to perform two tasks at the same time (dual task technique) – a digit span task which required them to repeat a list of numbers, and a verbal reasoning task which required them to answer true or false to various questions (e.g., B is followed by A?).

Results: As the number of digits increased in the digit span tasks, participants took longer to answer the reasoning questions, but not much longer – only fractions of a second. And, they didn”t make any more errors in the verbal reasoning tasks as the number of digits increased.

Conclusion: The verbal reasoning task made use of the central executive and the digit span task made use of the phonological loop.

Several neuroimaging studies have attempted to identify distinct neural correlates for the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad posited by the multi-component model.

For example, some studies have found that tasks tapping phonological storage tend to activate more left-hemisphere perisylvian language areas, whereas visuospatial tasks activate more right posterior regions like the parietal cortex (Smith & Jonides, 1997).

However, the overall pattern of results remains complex and controversial. Meta-analyses often fail to show consistent localization of verbal and visuospatial working memory (Baddeley, 2012).

There is significant overlap in activation, which may reflect binding processes through the episodic buffer, as well as common executive demands.

Differences in paradigms and limitations of neuroimaging methodology further complicate mapping the components of working memory onto distinct brain regions or circuits (Henson, 2001).

While neuroscience offers insight into working memory, Baddeley (2012) argues that clear anatomical localization is unlikely given the distributed and interactive nature of working memory. Specifically, he suggests that each component likely comprises a complex neural circuit rather than a circumscribed brain area.

Additionally, working memory processes are closely interrelated with other systems for attention, perception and long-term memory. Thus, neuroimaging provides clues but has not yet offered definitive evidence to validate the separable storage components posited in the multi-component framework.

Further research using techniques with higher spatial and temporal resolution may help better delineate the neural basis of verbal and visuo-spatial working memory.

Lieberman (1980) criticizes the working memory model as the visuospatial sketchpad (VSS) implies that all spatial information was first visual (they are linked).

However, Lieberman points out that blind people have excellent spatial awareness, although they have never had any visual information. Lieberman argues that the VSS should be separated into two different components: one for visual information and one for spatial.

There is little direct evidence for how the central executive works and what it does. The capacity of the central executive has never been measured.

Working memory only involves STM, so it is not a comprehensive model of memory (as it does not include SM or LTM).

The working memory model does not explain changes in processing ability that occur as the result of practice or time.

Early models of working memory proposed specialized storage systems, such as the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad, in Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) influential multi-component model.

However, newer “state-based” models suggest working memory arises from temporarily activating representations that already exist in your brain’s long-term memory or perceptual systems.

For example, you activate your memory of number concepts to remember a phone number. Or, to remember where your keys are, you activate your mental map of the room.

According to state-based models, you hold information in mind by directing your attention to these internal representations. This gives them a temporary “boost” of activity.

More recent state-based models argue against dedicated buffers, and propose that working memory relies on temporarily activating long-term memory representations through attention (Cowan, 1995; Oberauer, 2002) or recruiting perceptual and motor systems (Postle, 2006; D’Esposito, 2007).

Evidence from multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) of fMRI data largely supports state-based models, rather than dedicated storage buffers.

For example, Lewis-Peacock and Postle (2008) showed MVPA classifiers could decode information being held in working memory from patterns of activity associated with long-term memory for that content.

Other studies have shown stimulus-specific patterns of activity in sensory cortices support the retention of perceptual information (Harrison & Tong, 2009; Serences et al., 2009).

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Chapter: Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In Spence, K. W., & Spence, J. T. The psychology of learning and motivation (Volume 2). New York: Academic Press. pp. 89–195.

Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baddeley, A. (1996). Exploring the central executive. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 49(1), 5-28.

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4, (11): 417-423.

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory. Current biology, 20(4), R136-R140.

Baddeley, A. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual review of psychology, 63, 1-29.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). New York: Academic Press.

Baddeley, A. D., & Lieberman, K. (1980). Spatial working memory. ln R. Nickerson. Attention and Performance, VIII. Hillsdale, N): Erlbaum.

Borella, E., Carretti, B., Sciore, R., Capotosto, E., Taconnat, L., Cornoldi, C., & De Beni, R. (2017). Training working memory in older adults: Is there an advantage of using strategies?. Psychology and Aging, 32(2), 178.

Chai, W. J., Abd Hamid, A. I., & Abdullah, J. M. (2018). Working memory from the psychological and neurosciences perspectives: a review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 401.

Cowan, N. (1995). Attention and memory: An integrated framework. Oxford Psychology Series, No. 26. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cowan, N. (2005). Working memory capacity. Exp. Psychology, 54, 245–246.

Cowan, N. (2008). What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory?. Progress in brain research, 169, 323-338.

Curtis, C.E., & D’Esposito, M. (2003). Persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex during working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(9), 415-423.

D’Esposito, M. (2007). From cognitive to neural models of working memory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 362(1481), 761-772.

D’Esposito, M., & Postle, B. R. (2015). The cognitive neuroscience of working memory. Annual review of psychology, 66, 115-142.

Fell, J., & Axmacher, N. (2011). The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(2), 105-118.

Harrison, S. A., & Tong, F. (2009). Decoding reveals the contents of visual working memory in early visual areas. Nature, 458(7238), 632-635.

Henson, R. (2001). Neural working memory. In J. Andrade (Ed.), Working memory in perspective (pp. 151-174). Psychology Press.

Lewis-Peacock, J. A., & Postle, B. R. (2008). Temporary activation of long-term memory supports working memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(35), 8765-8771.

Lieberman, M. D. (2000). Introversion and working memory: Central executive differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(3), 479-486.

Osaka, M., Osaka, N., Kondo, H., Morishita, M., Fukuyama, H., Aso, T., & Shibasaki, H. (2003). The neural basis of individual differences in working memory capacity: an fMRI study. NeuroImage, 18(3), 789-797.

Serences, J.T., Ester, E.F., Vogel, E.K., & Awh, E. (2009). Stimulus-specific delay activity in human primary visual cortex. Psychological Science, 20(2), 207-214.

Smith, E.E., & Jonides, J. (1997). Working memory: A view from neuroimaging. Cognitive Psychology, 33(1), 5-42.